Obstacles are what you see when you are not focused on the goal.—OLD INDIAN ADAGE

Challenge of Business Growth in India

Many multinational corporations have struggled to get it right in India. These include big European and American brands such as Fiat, General Motors, Ford, and Electrolux and a host of Japanese companies including Sony and Panasonic. The Japanese exception being the Maruti Suzuki JV and to some extent Toyota. In contrast, Korean companies have been relatively more successful even though sometimes they entered India as many as ten years later than their rivals from other countries. I often wondered why. A Mckinsey study of the top 50 multinationals had shown that only 2% of their global revenue came from India. Whether these companies were from the for-profit sector such as Microsoft, IBM, GE, Apple, Philips, Siemens, etc, or representing not-for-profit knowledge brands like ASQ, PMI, etc, the story is the same, their revenues from India were around 1-2% of global revenue. They contributed to less than 5% of global revenue growth targets.

Cases of Success

On researching this question, it was clear that were some exceptions such as HUL, JCB, and Korean companies such as Hyundai, Samsung, etc whose leadership made a strong commitment to the Indian market even before they entered. They were clear that India is a market where they have to be successful and hence, they gave it everything they had. They started with an India-specific team that spent an extended period in India understanding the context. This team enjoyed the confidence of the Korean headquarters to take whatever local decisions were necessary to make the business successful. This gave them the flexibility to respond to the fast-changing Indian market.

Korean companies have been sensitive to the market by launching the products most appropriate for India. Remember that Hyundai changed its market entry vehicle from the Accent to the Santro when it realised that there was a huge market looking for an alternative to the Maruti 800. They have made product modifications to suit Indian conditions – they were the first to provide washing machines with the ability to restart from the same point in the event of a power outage. At the same time, they were careful not to dump old products, thereby, showing respect to the Indian consumer – remember that Ford and Hyundai started in India around the same time, but it took Ford years to recover from the wrong choice of an obsolete Escort model as their first product offering. Korean companies made considerable efforts to build their brands in India. And, they paid a lot of attention to execution, working closely with their Indian teams.

What Enables or Disables Success?

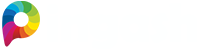

The challenge of the Midway Trap is conceptualised in Fig 1.0. It is universal and faced by all International organizations trying to enter Indian markets. The Midway Trap phenomenon explains as to why major American and Japanese multinationals lost out to the Koreans in India. It was primarily due to their efforts to push high-end products at the Indian market at international prices, even though only a small proportion of the market can afford them; short CEO tenures which mean that a CEO is ready to leave India before (s)he comes to grip with the Indian market; and verticalized reporting structures that require managers in India to report to global product divisions, which results in the Indian market never getting the attention it deserves.

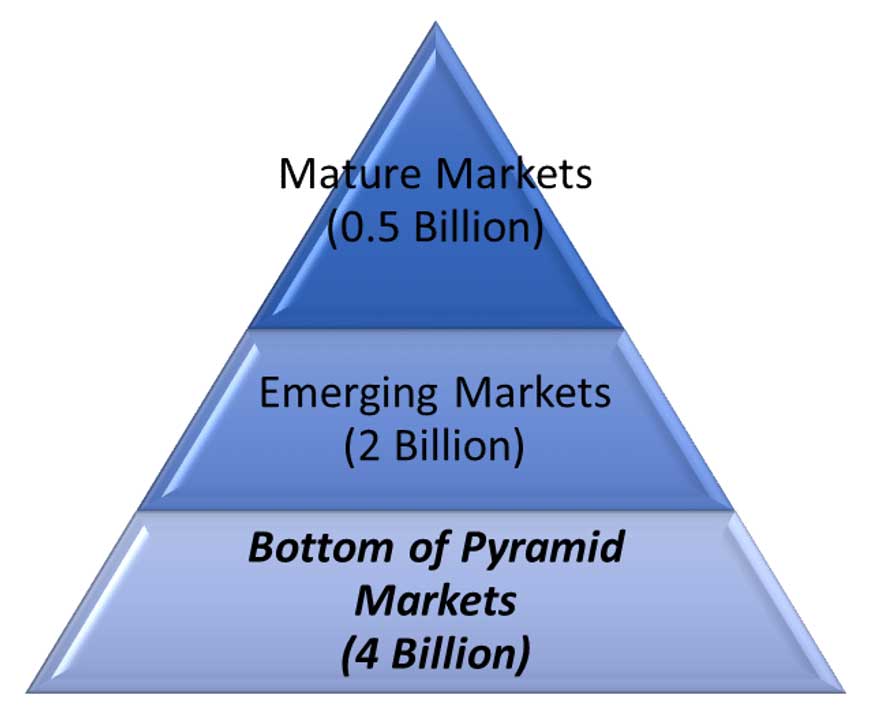

So, what should multinationals do to make a success of India? They should make India a strategic priority, and give India a special geographical focus outside the product division structure. They should make sure they avoid the “midway trap,” straddle a larger part of the market pyramid structure through innovations in their business models and products that are suited for India and not limit it to the top of the pyramid. At the top of the pyramid, everyone is trying to skim the cream hence competition saturates the profit zone fast. They should not get stuck in the small upper end of the market which faces erosion of profitability and growth. However, this requires a lot of courage and leadership will make a distinct shift away from a ‘revenue mindset to an opportunity mindset’ and willingness to be flexible to adapt their existing global business models and products, short-term sacrifices for long-term gains.

The selection of the CEO or Country Manager to lead the Indian operations is critical to its success. He or She must be a proven senior leader with entrepreneurial instincts drawn from a General Management background. A functional mid-level leader drawn from a sales or marketing background, reporting back to the sales or marketing head of the parent company HQ, mandated to push the global model and products is usually the choice of most International companies starting up in India due to sales focussed mindset. It may lead to short-term success for 3 to 4 years but eventually runs into the Midway Trap when the opportunities at the Top of the Pyramid (TOP)-Mature markets (Fig 2.0) saturate and the local leader either lacks strategic business abilities to innovate and go beyond his or her functional expertise or doesn’t get the support required from HQ to innovate and execute relevant business designs that may be beyond the realm of experiences of HQ but suited for Indian markets and customers.

The Market Pyramid: Top, Middle, and Bottom of the Pyramid

Considering India’s case, the BOP market has over 924 million with a purchasing power parity of rupees 6,550 thousand crores. There are 114 million households in India at the bottom of the Pyramid. The number is 76 percent of the rural population and 60 percent of India’s total population. So, suppose a marketer in India is not marketing to BOP. In that case, it is only selling to 60 percent of the population. This number becomes vital when the bottom of the pyramid population is spending about 310.5 thousand crore rupees on housing or equal to 48 percent of India’s national housing market.

Hence, if we don’t consider the bottom of the pyramid marketing, you are unfortunately ignoring a considerable chunk and many opportunities.

The most prominent example of this approach is General Electric, which appointed John Flannery, a senior Vice-President of GE, as India’s CEO in 2010 with the mandate of growing rapidly in the country. Flannery not only reported to the Vice-Chairman of GE but had a separate budget, cutting across verticals, to do what was necessary to succeed in the Indian market. It made a difference to GE’s operations in India.

Most MNCs, after initial days of quick success and euphoria through sales of existing products, enter into the Midway trap where growth is determined by the industry tide; the driving force is no longer with the company. Only those companies who can get out of this frustration zone (Fig. 1) can move on to the market leadership position. One oft-repeated but still missed out point is that MNCs consider India as an extension of their own market, and are surprised and distressed when they find that it is not so. This is so as most MNCs hand over the responsibility of the Indian market to the global sales or international business unit at the corporate. Indian market is not ready to accept most goods, and sales leadership has many other markets, more amenable to their goods. Thus, India continues to rank much low and at times disappears altogether from their radar. Rather, what a complex market like India needs is an entrepreneurial general manager, reporting directly to the CEO or similar top management of the MNC to ensure unwavering attention, appropriate and timely decisions, and most importantly, investments with longer payback periods.

Beyond Strategy to Resilience: All About Leadership Courage

JCB a European organization, a manufacturer of earthmoving equipment is a privately-held company, headed globally by an Indophile. Its ability to take a strong position on India would appear to be more like the typical Korean company’s decision to give India everything it had an approach not easily reproducible in the typical MNC.

Going beyond the strategy piece, there is the issue of leadership companies seeking success in India must address for sustainability. The need for MNCs to build a strong leadership pipeline in India holds the key. Here, the prime example is Hindustan Unilever (HUL), which advocates the crucible of mentorship as the best way to train leaders, similar in many ways to the Tata Group an Indian MNC. Courage and Resilience are the number one characteristics one needs in an MNC subsidiary CEO for India. The chaos in India is not for the faint-hearted. Only people with courage will have the perseverance to stay the course, fight to win, and, yet, not compromise on core values.

We see it quite often that the revolving door starts spinning fast as leaders come and go both at the parent organizations HQ as well as the Indian entity. The parent companies start restructuring in an attempt to grapple with the Midway Trap without understanding the real issue. It is akin to shifting the chairs on the deck of the Titanic.

Ultimately without any significant success through cosmetic maneuvers, the companies whose leadership lacks courage, creativity, and vision usually decide to scale down their local operations due to their inability to scale the Midway Chasm with innovative thinking. They accept satisfactory ‘Under-Performance’ as their fate and carry on an existence of insignificance from standpoint of both business and societal impact. This unfortunately has been the state of the majority of International companies in India they are unable to come out of their mindsets conditioned by their experiences in developed economies. My professional experiences have covered the response of organizations to the Midway Trap spectrum, from radical success through the high degree of innovative thinking and adaptability at Tata Honeywell the JV in Automation, that ultimately set the benchmarks for innovative leadership at parent Honeywell creating paradigm shifts in mindset. In contrast on the other hand, ASQ a US-based not-for-profit knowledge brand of the highest credibility, succumbed to the gravitational pull of the Midway trap despite the best local talents for all the reasons associated with leadership inertia at HQ already stated, forcing it to scale down the Indian operations to an insignificant level societal and business impact. Incidentally the current CEO of Honeywell USA from India, who rose from the ranks of the Tata Honeywell JV, which became the talent hub for the parent company providing many senior leaders across Honeywell globally—similar to the HUL model of crucible effect.

Conclusion and Lessons

Of course, a company’s willingness to make these major changes would depend on its evaluation of its future business prospects in India. India’s opportunity story is always a hard sell. However, mastering India not only helps a multinational company position itself for one-sixth of the world’s population but also to succeed in smaller “India-like” markets, where ‘Chaos comes blended with Opportunity’.

Doing business in most emerging markets is tough. But, both in its potential and its challenges, India is the prototype of many other emerging markets. The market potential of all such markets is tempered with varying combinations of corruption, volatility, chaos, governance issues, weak institutions, and poor infrastructure.

However, India with its unique amalgamation of huge potential, substantial managerial capability, decent talent pool, and developed institutions acts as a cauldron for MNCs to hone their strategy. There is not one India, but many India co-existing that demand atypical strategy by MNCs. Based on annual income data, the entire country can be stratified as a flattish pyramid with a fat base. The small affluent segment at the top – “Australia at the top of India” as Steve Ballmer of Microsoft calls it, resembles the markets of the home country, and thus MNCs feel most at ease to sell global products at global prices.

But, their box of ready templates fails to deliver as MNCs try to deepen their presence in the price-sensitive, quality-conscious, features-demanding middle market. Cracking this middle market requires considerable innovation, who perhaps wants “70 percent of the value of the global product at 30 percent of the price”. Then, there is the bottom of the pyramid, who survives on less than $2 a day; they represent not an opportunity to earn a fortune, but “an opportunity to earn trust and goodwill through corporate social responsibility and shared value initiatives”. The big question to be addressed is—are the MNCs ready to take on the India challenge with a change in prevailing mindset and the resilience to persist or opt for the easy way out—By Accepting Satisfactory Underperformance—when faced with the Midway Trap.